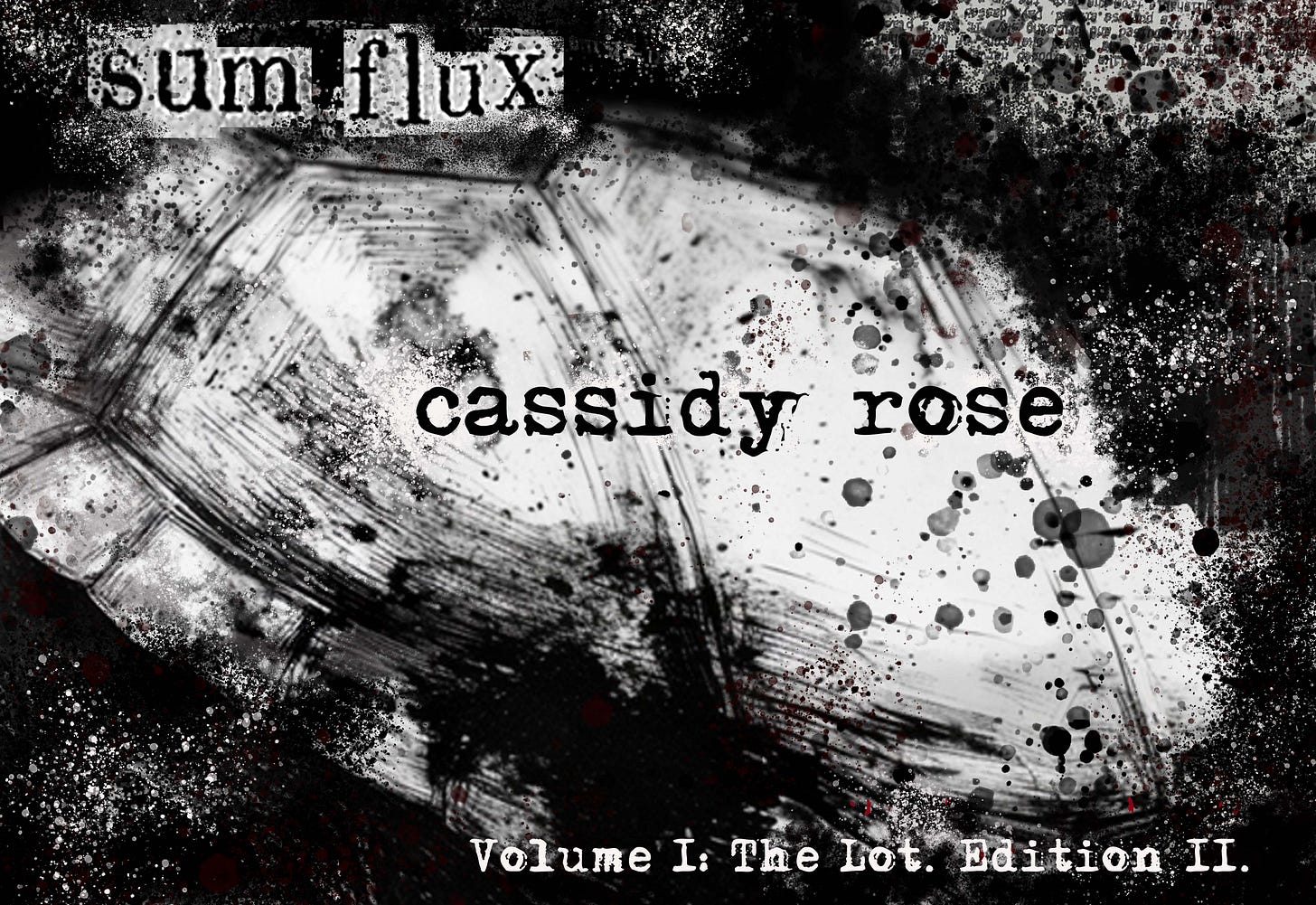

This piece is part of The Lot, the first volume of SUM FLUX. Featured in Edition II, this work is one of eight contributions to this edition. Read more about this zine and its theme here: https://sumflux.substack.com/p/volume-1-the-lot.

Her father was late to pick her up. Sitting alone on the parking lot curb amidst the clatter and clash of children rushing into waiting cars late. Straggling teens pushing and pinching and groping each other against the bike racks. Late, setting summer sun on the cracked asphalt, late. Shadows becoming shorter and then everything becoming shadow. Late. Parking lot floodlights flickering on. Late. Even the janitor’s gone home late. Growing hungry and growing angry late. Pick up her bag and walk home in the darkness, sweatshirt hood pulled over her head to discourage any passing cars that may have slowed for a child on the cusp, kind of late.

Stomping through the back door, she found the house unnervingly dark and silent. The pulsing indignation in her chest chilled rapidly into fear.

Dad? she called.

I’m here, darling, a tight and raspy voice responded. Just having some issues.

She followed the broken tightrope of a voice deeper into the bowels of the home to her father’s bedroom. She stumbled into the room, nearly tripping over something hard and rock-like at the foot of the door.

Why did her father never come to pick her up? He couldn’t, because sometime after this morning, after she’d slammed the car door shut without saying goodbye, he had turned into a turtle. He now sat morosely at the door, unable to turn the knob.

He was no ancient tortoise, but no piddling school-fair amphibian, either. Medium-sized, he would have brushed her shins were she not backing away from the smell of herpetarium which filled the room, peaty and grassy, dank and urine. Never in her life would she forget that smell, would hold her nose on the toilet, to avoid the overwhelming waves of shame that the smell of piss set free.

Just some issues, he repeated. Not to worry.

She pulled the door open further and watched her sad turtle father plod out, although for a moment, she considered shutting the door tight.

***

She woke up late, unaccustomed to the quiet house, bereft of kitchen clatter and the radio, the usual soundtrack to her mornings.

Are you ready for school, honey? he rasped at her as she slid into the kitchen for a granola bar.

Of course, she wasn’t ready for school— she’d only just woken up, and her father was now a turtle. But she nodded anyway, nodded downwards, instead of upwards as she was used to, nodded because she knew he could not stand to have her there, witnessing his slowly-churning pince- mouth try to stammer out an excuse for Why All This Was Happening.

As her father could no longer drive, she had to walk, and as such, she got to school just as the bell rang and she was lost in the masses of children swirling from parking lot to building, swept away as if she was just another child who was not the daughter of a turtle.

Her health class teacher was an excitable young person who delivered the most dire news in an untenable upbeat patter.

Your bodies, minds, and souls are undergoing all sorts of changes right now, the teacher delivered, bouncing on buoyant heels. You will be irrevocably different in a few years. Your childhood is ending. Grasp it, if you can, for these are the years you’ll be dreaming of for the rest of your lives.

And then, delightedly: Here’s a worksheet. Fill in ten changes that occur in puberty. These do not have to be changes you have experienced, although they might be, and it is fine if they are.

In biology, her class vivisected fifteen large-ish lizards in small groups. She was the first to find the heart, which was the size of a worn-down eraser head. For her efforts, she was awarded a star, although the teacher was out of stars, so she was actually promised a star come Monday, although she did not have high hopes for this, not with the way her life was going right now.

The hallways were anxious with the nearness of summer: the lockers sweat and wiped their brows, the ceilings swelled irritably pregnant with watermarks. The promise of another semester ended. Chatter and change. What’re you doing this summer? I’m going to camp. I’m going to see my grandma, we always go. Rockies. Hawaii. Spain. New Jersey. Probably nothing. Swimming camping sleeping. The beach the bed the shore the forest the drive the highway the farm stand. Ice cream watermelon popsicles lemonade sunscreen sweating fucking filth and fever. She felt it all, knew it all, was heavy with what would happen, what was happening, a roiling, unbounded tsunami. The ocean in her head– endless in every direction.

***

Daughter, how was your day? asked the turtle, unconvincingly father-like. They were eating pizza. She imagined him dialing the phone with his clumsy feet, or his beaky nose, fumbling at the numbers. Misdial after misdial. All day it took him, probably, to order this pizza, because he could not cook her meals–not anymore, not like he did yesterday.

How was yours, she swatted back. It was not a question, and she did not mean it kindly. It occurred to her, once again, that she did not have to open the door for him this morning, would not have to open the door tomorrow morning.

How long would this last, though? Maybe it was natural, maybe everyone else’s parents were doing the same thing, and nobody wanted to mention it. because they, too, felt eons of shame. Or maybe, it was so normal that nobody was bringing it up because there was nothing really to mention at all. Maybe becoming a turtle was a symptom of middle age, like becoming a prophetous ocean was a symptom of adolescence. At least in her experience.

Maybe it was a phase, maybe tomorrow, she wouldn’t need to think bitter thoughts about locking her turtle father in his reptile room, because tomorrow, he would be tall and unfurrowed and cooking something delicious. His voice would be like fresh rubber bands, and his arms would be warm-blooded and welcoming. Tomorrow, she would not feel so freshly shaved, so prickly and covered in small wounds. And she would know very little, but feel great masses of joy, each one a balloon pulling at her limbs and lightening the load. She clings to tomorrow, longs for its embrace, hopes it will look like yesterday.

She and her father sit and sit and sit, as the sun fades and leaves them once more. Neither one will be the first to leave the table. He looks at her and is astounded by the fierceness of her presence. He has a lingering thought that his eyes are not strong enough to perceive her entirety, that she is thrumming loudly past the edges of his vision.

Dad, she says finally. If I were the only changing thing in the world, I could just barely handle that.

He nods. He knows. He learned that one himself once.

"He has a lingering thought that his eyes are not strong enough to perceive her entirety, that she is thrumming loudly past the edges of his vision"

-love the atmosphere here

Astounding. Seriously good writing.